Participatory Video: Our Key Steps

These are the key steps we followed for the Participatory Video with Most Significant Change (PVMSC) process. The method may need to be adapted according to the group, situation, time available, and topic.

Contents

- Introduction

- Ethical Approval

- Recruiting Participants and Getting Consent

- Delivering the Sessions

- Storytelling

- Storyboards

- Reasserting the Community’s Values and Story

- Who is the Film For?

- Filming Tools and Techniques

- Learning through Hands-on Experience and Peer-to-Peer Learning

- Reflective Filmmaking and On-the-go Learning

- Inclusive Editing and Shaping the Narrative

- Film Screening

Introduction

The Participatory Video with Most Significant Change (PVMSC) process culminates in a film that is developed, filmed and edited by the group – and each individual step along the way is important. At its core it is about storytelling and encouraging the participants to describe their own individual stories. At the same time, we teach and work with the skills to tell this story through the medium of film.

The following is a run through of the main activities we carried out during the PVMSC process rather than a prescriptive day by day description. It may need to be adapted according to the group, situation, time available and topic. There are reference materials provided here that can offer much more detail.

Ethical Approval

The research activities proposed in this study were approved by Swansea University Research Ethics Committee (REC). We used a process of informed consent to ensure that everyone understood all research activities and if, how, why and where the film footage could be used.

Tip: All studies that involve people as participants require a research ethics committee review. This is to ensure that research participants are protected in terms of their rights, safety, dignity and wellbeing.

Due to the nature of the PVMSC activities we used an ongoing consent process for the different steps involved (for example participants may want to take part in PVMSC activities but not wish to share any films produced; or participants may want to share films further including within the wider community and/or via social media – potentially globally.)

Recruiting Participants and Getting Consent

We wanted to recruit a diverse group of people to the study representing different genders, socio-economic status and ages. Participants had to be over 18 years of age and:

- Local residents of Khuded village

- Able to provide informed consent

- Able to communicate in Marathi and/or the local dialect

A local non-governmental organisation helped to recruit the participants. The Gram Panchayat (village council) and Tata Institute of Social Sciences were also all involved with the project and helped to share information with community members.

A group of interested individuals attended an initial meeting to ensure that informed consent could take place. The researchers explained the activities and provided participant information sheets (translated into the local language), which were read out to those unable to read. Their right to withdraw from the research at any point was emphasised.

Thirteen villagers agreed to take part and all attended a minimum of seven PVMSC sessions, with four attending all 10 sessions. Participants included:

- 4 women and 2 men aged 18-35

- 3 women and 1 man aged 36-59

- 1 woman and 2 men aged 60+

Delivering the Sessions

We delivered 10 sessions between November 23rd and December 4th 2022. All sessions were held in the afternoon from around 14.30 as this was the time most convenient for the group (after many of the main essential daily activities had been completed and before the evening food preparation and family meal). The sessions lasted between 90 minutes and 3 hours with a planned break and with refreshments provided. All sessions were held in the Solar OASIS building – though lots of filming activities were out ‘on location’ around the village. See resources page for a more detailed plan of what was covered in each session.

In our initial ‘warm-up’ sessions we used ice-breakers and activities that helped familiarise the group with the phone camera and equipment. This helped to create an environment of trust and respect where participants were able to ask questions, make mistakes, learn from each other and feel comfortable with the equipment we were using. There are some examples of ice-breaker games here.

Storytelling

Through sharing their stories, individual participants were able to see the bigger picture and start thinking about how their stories could be woven together into a shared narrative. Through collective decision-making, participants worked together to determine how the selected story/stories could be included in the final film(s). Additional tools such as the ‘River of Life’ game helped to develop the story and to bring out important details and themes that might not have been immediately apparent. Find out how to play the ‘River of Life’ game here.

Tip: Story telling is a key part of the PVMSC process. When we listen to someone else’s story, we begin to empathise with them. Individuals may describe different problems, or other people may add their unique perspectives to the conversation, which can help to expose us to new ways of thinking. It is important to listen to each story carefully, discuss any issues that arise, and work together to find possible solutions (if appropriate). By listening to each other and sharing experiences, we can build a healthy dialogue, and create a space where everyone has a voice.

Storyboards

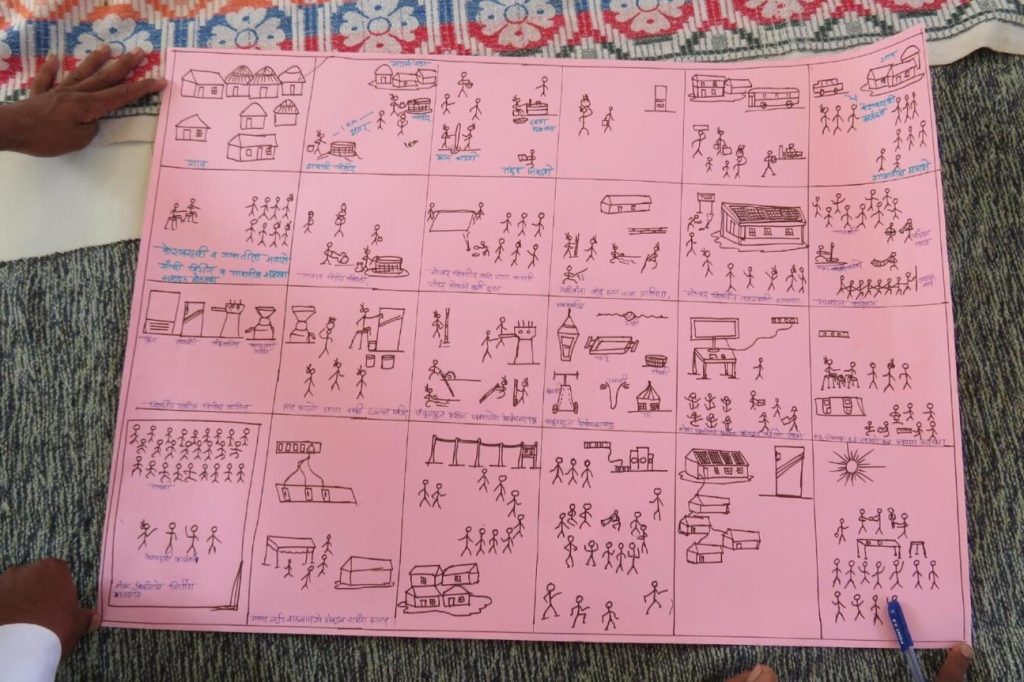

A storyboard is a series of drawings or images that help tell a story in a visual format. It’s like a comic strip that shows the key scenes or moments of a story, and can more easily be altered before filming or creating the final piece. It also helps the storytellers to visualise their ideas and bring them to life.

The group’s storyboard was developed once they had agreed what they wanted to include in their story. They used it to plan and organise the story they wanted to tell. Each drawing in the storyboard represents a specific scene or shot to be filmed, and they are arranged in the sequence that will show how the story unfolds. The drawings can be accompanied by brief descriptions or notes that explain what is happening in each scene or that a narrator may want to include. This was the case for some of the shots that the group decided needed more clarification – or to ensure key information was shared. Depending on how detailed the group wants the storyboard to be it can also allow the videographer to see the composition needed for each shot (for example include a close up or distance shot and even about lighting). Added detail can include prompts to show how different scenes connect, detail required and the pace of the story.

Initially when we started the storyboarding activity they had some inhibitions, but then slowly they started drawing and sharing ideas. They seemed quite comfortable using creative ideas to express themselves. Many used traditional Warli art styles, using triangles and shapes to represent the story in a way that was traditional within their culture. They are the owners and writers of their story, expressed in their own words and styles. One member of the group who was a Warli artist led on drawing the main storyboard, but everyone contributed in some way. It was a combined effort to tell the story as each box was completed with comments and inclusions suggested from the others.

There were different literacy levels within the group (some of the older adults in particular may not be literate), and so this way of telling a story is something that people were more comfortable with, sketching or directing as they preferred.

Reasserting the Community’s Values and Story

Throughout the process, we recapped and discussed the importance of keeping the story true to the group’s experiences of using the new technology and how this had made a difference to them.

Continually refocusing the film on the community benefits or issues gave valuable insights into how the group had adopted the new technologies. They wanted to demonstrate changes that were taking place between more traditional methods of rice husking and grinding for instance and the place of the new equipment that performed these tasks.

Who is the Film For?

It was important when creating the film for the group to decide who would be the ultimate audience. This could have been just the participants, the local community, surrounding villages, and /or decision makers if they wanted to raise concerns or seek additional support to achieve some of the recommendations and desires that they had identified.

This was discussed fairly early on in the process – as it is useful to have a target audience in mind to shape how you tell a story – but it was not decided until later on in the sessions. The PVMSC process in this instance was more about achieving consensus, learning skills and having the opportunities to use them as well as making steps towards empowerment. Determining the film’s final target audience was an important but moveable aspect of the journey. By contemplating the messages they wished to deliver over some time, they honed their storytelling skills and gained a deeper understanding of the power of their own narratives. This exercise provided greater clarity, impact, and purpose.

Filming Tools and Techniques

From the first session, the group was introduced to the filmmaking equipment (phone cameras and software) through interactive games and activities. Basic techniques, such as pressing the record button, framing shots, and understanding pause and on-off functions, were taught as the sessions went on.

All participants were encouraged to take part in all the activities involved in the filmmaking process, including story, filming, editing, and screening. Games helped to infuse an element of fun and encourage a positive attitude towards mistakes. Not everyone in the group had previous access to a camera or a smartphone, so it was important to encourage everyone to use it without fear of damaging the device. The ‘disappearing game’ became a source of excitement and laughter (find out how to play it here).

As the process unfolded, the group ventured ‘into the field’, filming different aspects of the storyboard. It was during this phase that their skills began to develop. Notably, participants who initially showed interest and enthusiasm started to explore their potential further. The prospect of seeing themselves on a larger screen and being part of a video was a big motivator.

Tip: The participatory video filmmaking process supports individuals to be active contributors in documenting their own stories in their own words and images.

Learning Through Hands-on Experience and Peer-to-Peer Learning

The approach of teaching participants to teach others worked well. Individuals started with different skill levels and confidence with the equipment and so this meant that others had to adapt and use different ways of explaining and showing the next participant what to do. This method strengthened their own understanding, communication skills and facilitated shared learning. It was not always the case that everyone wanted to take part in all activities equally and once they had ‘had a go’ some were then content to sit back and let the others (often the younger members) take over the responsibility of filming while they contributed to the directing or editing.

Reflective Filmmaking and On-the-Go Learning

During the filming process, the entire community were able to observe the activities of the group and could find out more about what was going on. What initially started with a few confident individuals stepping forward soon transformed into a collective effort. Use of devices and tools from the beginning, coupled with encouragement from researchers and the group to actively participate, played a pivotal role in this transformation. It was satisfying to witness the organic development of a supportive environment where individuals corrected each other’s techniques, from holding the devices to framing shots. Different people from the group took on roles of director, directing the person behind and in front of the camera.

One of the critical factors that contributed to the community’s progress was the ability to review footage at the end of the sessions. Whether on the phone’s screen or a computer, the community members could see their work in real-time. Interactions within the group became lively and enthusiastic, demonstrating the engagement of participants in the process. It was evident that they were immersed in the filming process, eager to learn and improve techniques.

As participants ventured out into the community, capturing aspects of the stories they wanted to tell, they encountered some challenges. For example, participants had technical queries with questions like, “Why is the footage blurry?” or “How can we adjust the settings?” This sparked discussions and ‘on-the-go learning’, which fostered a deeper understanding of the technical aspects of filmmaking.

The researchers took on the role of uploading the footage taken on a daily basis to a central computer and hard drive to ensure that we had a copy of all the footage in case of any unintended deletions during the process of editing.

Inclusive Editing and Shaping the Narrative

The editing phase was a collaborative process. We demonstrated the editing process from an early stage in the process – for example by playing the disappearing game clip and demonstrating how music could be incorporated into the filming. They learned how to cut scenes, rearrange sequences based on the storyboards, and contribute to the overall storytelling process.

While some already had film editing experience (for example use of YouTube shorts on phones) and were interested in gaining more skills, the majority were happy to watch the filmed clips and direct what should or should not be included.

The inclusive nature ensured every individual had a voice in shaping the final video, resulting in a film that represented the collective vision detailed in the storyboard.

Film Screening

PV has been used in other research or evaluation situations to include a final screening of video(s) to wider stakeholders, which can further create opportunities for social and political influence through wider and progressive engagement. The participants in this situation wanted to hold a public screening but as a celebratory event and to show others what they had produced. They did not want to invite other stakeholders and/or open up a wider discussion afterwards. Instead, they planned and prepared a celebratory event that included refreshments for attendees and presentations to the researchers, participants as well as the main event – the screening. Copies of the film and additional footage taken were left with the community so that they can re-watch at a later stage.

Funding Source

Determining Equitable Benefits: Achieving Transitions in renewable Energy (DEBATE) is funded by British Academy Small Research Grants scheme SRG22\220462 (2022)